‘Blank City’ director Celine Danhier on New York’s No Wave movement, starving artists and the ensuing gentrification

Auteur: Alexander Sellers

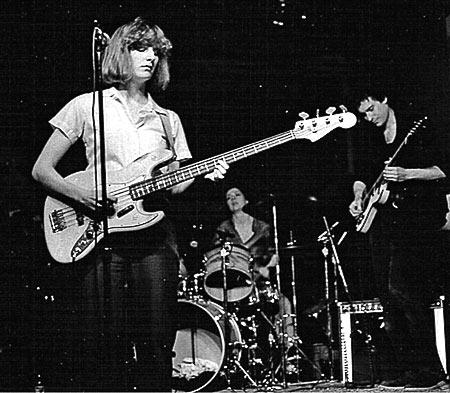

Late '70s New York City. Whether you had the gall to live there or not, it’s a time and place that evokes a lot of images. Within the seedy downtown neighbourhoods, abandoned apartments and violent streets, the city was bustling with a creative energy that now lives but famously in film. Indeed, after thirty years of influence but surprisingly little documentation, the label ‘No Wave’ has since come to represent the group of filmmakers and musicians captured by the vista and attitude of their often nasty and always unique home.

Musically, the period has fared far better in the indie history books, with Patti Smith, the Contortions and Sonic Youth all well represented. But cinematically—not so much. Driven by the motivation to pull this under-represented, underground film movement into the spotlight, Blank City documents the fiery creativity of the city’s dedicated filmmakers. It features interviews with the more well-known (Jim Jarmusch, Steve Buscemi) and the often forgotten, all scraping together change to buy a Super 8 and get to shooting as soon as possible.

We had a chat with Paris-gone-New York director Celine Danhier, director of the documentary to discuss her work in anticipation for its ongoing screening at the Cinéma du Parc. The conversation covered her constant love for NYC, the starving artist and even a little outside opinion on our own vibrant ville.

So how did you first get into this underground film movement as a director? What about '70s and '80s New York City film so compelled you?

First, I think I was always drawn to New York City, even when I was a kid and a teenager. I watched a lot of movies centered in New York, and I felt inspired by the city itself. I remember when I was just seventeen years old and I watched the films of Amos Kollek, Sue Lost in Manhattan or Bridget. I really fell in love with this strange and dark and very attractive New York. Then when I was living in Paris, I started listening to a lot of ‘No Wave’ bands—Lydia Lunch, James Chance & the Contortions, DNA. I knew this label ‘No Wave,’ but I didn’t really know what it meant. And I became very intrigued when I heard the label used for film. I wanted to know what made up a ‘No Wave’ movie.

So looking into it, I found it difficult to find anything about the movement. Eventually, from friends, I started tracking down some of the films and discovering them at retrospective film events in Paris—such as the first films of Jim Jarmusch, Susan Seidelman, and even Charlie Ahearn. But when I wanted to track down even more films and talk to the filmmakers, it became too difficult. So I moved to New York and started doing my work and research here. And it was all a very quick process, because I moved four years ago and started working on the film about three and a half years ago.

What was your selection process for the footage in the film? How did you come up with your narrative direction for a movement that jumps around quite a lot in itself?

The order came about very organically. It started with the so-called ‘Blank Generation’ in 1976 and then there was this movement of basically teenagers forming the ‘No Wave’ filmmaking movement itself. So those were filmmakers like Amos Poe in 1976—and then a whole medley of them—Ferrera in ’78, Eric Mitchell in ’78, and then Jim Jarmusch, who released Permanent Vacation in 1980. But the Cinema of Transgression Manifesto happened later. Nick Zedd wrote the Manifesto in 1985, so that comes in later in the film. So yes, it was all pretty organic and chronological.

Part of the early formula for this movement was a complete lack of funds. Would you say that especially fueled their creativity? And by that same token, would more money prevent the same kind of inventiveness between these filmmakers?

Well that was just the truth for them at that time, and actually New York itself was almost completely bankrupt. John Waters said it was “anarchy in the streets.” So out of that you actually had a lot of freedom and collaboration. People shared that aesthetic of images shot with a lack of technique, a kind of similar sensibility. So surely having no money actually helped because the movement was so pure. They weren’t tied up in all the economic factors of filmmaking.

As you show in the film, the movement reacted to number of influences—French new-wave, the Beat generation, political trends of the era—but also had a nihilist attitude of forgetting the past and starting completely anew. How do those two themes coincide?

Well, these guys definitely wanted to break all the rules of traditional filmmaking. But it’s true, before them there were the Beats and the Avant Garde work of Warhol. Warhol didn’t really show any stories though, so these filmmakers went out and wanted to express themselves differently in film. So they were inspired by what they saw from the previous generation, the Beats, Warhol and even French New Wave, but the real desire was to start something new.

Toward the end of the movie, you seem to point out pretty clearly that the same energy no longer exists in New York after its gentrification. But do you see it outside of the island of Manhattan, in Brooklyn or Queens perhaps?

Yeah, I think that’s the great thing about New York. It’s always shifting around. Right now you see that Manhattan is such an expensive, gentrified place and you have the feeling it has lost some of its uniqueness. But at the same time, you have a lot of parts of Brooklyn that have very cheap places to live. I mean, even if Manhattan costs too much, the energy is still there outside of it.

But now, you don’t even need to be in one place. Back in the '70s and '80s, being in New York was so important because all the artists were living together there. Now you can go really wherever you want because of technology. You can share your art and reach a wide audience today such as you couldn’t do before, without even living close by.

Sure. But are there still some cities—in your eyes—with the same kind of close-knit energy that New York had back then? Perhaps Berlin—as some people think, or here in Montreal—as we’d like to think?

Yes. I thought I would get that same feeling from Berlin, but I went last year and was actually kind of disappointed. Though now I’ve heard from a lot of people that Detroit is its own kind of run-down city much like New York was in the late seventies. So I’d love to say Detroit, but to be honest it’s only because I’ve heard that from a lot of others. But yeah, it’s definitely a place where you can just go and buy an abandoned house for a couple of bucks and live on the cheap. I was only in Montreal for one day—a pretty short time, but I really liked it. I really like what’s happening there in terms of the scene and all the arts communities. Yeah, it would say it’s a very cool city.

Blank City Official Trailer from Celine Danhier on Vimeo.

Cinéma du Parc | 3575 Du Parc | cinemaduparc.com