The ongoing Cartooning Calamities! exhibit offers a fascinating glimpse into the history of Quebec

Auteur: Michael-Oliver Harding

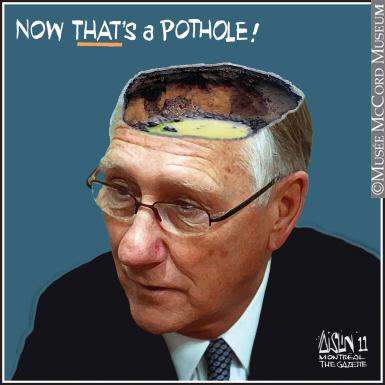

Now that's a Pothole!, Aislin (alias Terry Mosher), 2011, © McCord Museum

Exactly, it’s nice to know that I still make them a little nervous! (laughs) But you can always just put it up on Facebook, so the Internet is an oddly liberating force on this thing.

Depends on where you are. I think it’s still very effective here in Montreal, because it’s such a political city. Montreal remains one of the best cities to be an editorial cartoonist in, because of the fact that we have 4-5 daily cartoonists here. New York only has one. L.A. only has one or two, I think. So it depends on where you are, and the political activity of the city. I think other cities are very nervous about cartooning, so it’s sort of the first to go when the cutbacks happen, and they want to avoid any controversy.

Idi Amin, Aislin (alias Terry Mosher), 1977, © McCord Museum

Imagine…Fourteen Flowers, Aislin (alias Terry Mosher), December 9, 1989, © McCord Museum

I delight in the fact that none of us are perfect, and that we all make mistakes. Whether it’s politicians, you or me, or the average person on the street. I think I’m at my best when I’m portraying that sort of thing happening. It’s fun and that’s when I really enjoy myself the most.

The end of the world occurred on May 2, 2011!, Éric Godin, 2012, © McCord Museum

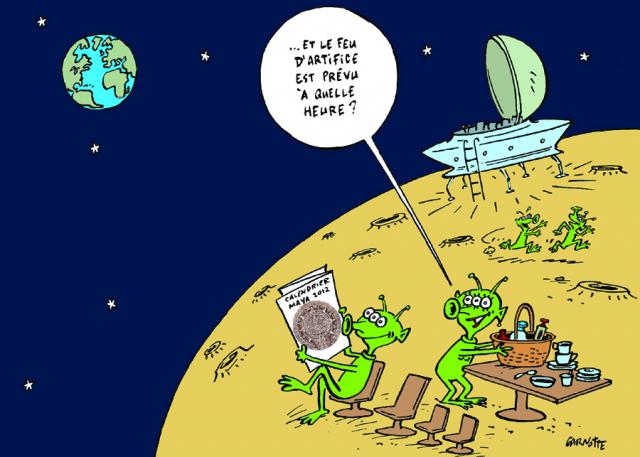

2012 Mayan calendar, Garnotte, 2012, © McCord Museum

I now draw my cartoons for how they look on a computer screen as opposed to how they look in a newspaper. And I just simplify it so they jump off the screen. If you look at my cartoons from the past two years, the colour is very deep, very contrast-y, so that when you see it on a computer screen, it really catches your eye. And that’s where all comment is going. A day will come in 2-3 years when more people will be looking at my work on a computer screen than they will in the newspaper. The numbers are increasing that rapidly.

Cartooning Calamities!

Until January 26, 2013

McCord Museum | 690 Sherbrooke Street West | mccord-museum.qc.ca